In this episode, Vanesa and Ian focus on sustainable theatre practice after Vanesa’s visit to the National Theatre event on the 14th November in London, where the Theatre Green Book took centre stage in an incredible event. They unpack the discussions, the international perspectives, and the sense of collective responsibility that shaped the day.

Ian reflects on his own past involvement with the Green Book and the broader questions it raises for productions, buildings and operations, as well as his experience with the CSPA in Canada. Together, they also explore what these ideas mean for Venue 13 as it develops, and how their upcoming non-profit Future 13 will put these principles into practice.

They also bring you this week’s CCTA reading: SO BEAUTIFUL TODAY, SO SUNNY by Marcus Youssef with Seth Klein.

CCTA Plays Featured:

So Beautiful Today, So Sunny

by Marcus Youssef and Seth Klein

Read by Ian Garrett & Vanesa Kelly

Show Links

- Theatre Green Book – https://theatregreenbook.com/

- Climate Change Theatre Action – https://www.climatechangetheatreaction.com/

Additional Media

Transcript

Ian (00:15):

Hello and welcome back to Podcast 13. This is episode four. I’m Ian.

Vanesa (00:21):

And I’m Vanesa. Thank you for tuning in again, whether you’re a longtime listener or new here, we are just so glad to have you with us.

Ian (00:28):

In our conversation so far, we’ve talked a lot about performance psychology and global design from world stage design to Team Lab. This week we shift the lens to the foundations of sustainable theatre itself.

Vanesa (00:39):

Right, and this is also because I recently went to an event at the National Theatre focused on theatre Green book, which is a global challenge for theatre makers to reduce the environmental footprint. It really got me thinking, and Ian has an especially interesting perspective having contributed to the Green book, in the past himself.

Ian (00:57):

So today we’re reflecting on sustainability in theatre, not just in the work we make, but in how we make it productions, buildings, operations, and what that means for Venue 13 and our plans for our future nonprofit venture, Future 13.

Vanesa (01:10):

But first,

Ian (01:11):

Today we’re going to be reading so Beautiful Today, so Sunny, which is a collaboration between Marcus Youssef and Seth Klein. The inspiration for this verbatim piece is inside of the piece itself, policy analyst and climate activists, Seth Klein is Marcus’s neighbor. Over the last few years, they’ve become friends as each of them approach 50 and navigated transitions in their work lives. Part of Seth’s Change was leaving his full-time job to write a good war mobilizing Canada for the Climate emergency, which is a book that uses Canada’s historic national mobilization for World War II as a model for responding to the climate crisis. A note on this play, the characters are friends consciously choosing to have this conversation and knowing that it will be made public. It’s noted that the actors can feel free to include the audience if as or when it feels right, maybe particularly when the characters seem to acknowledge that are speaking publicly. The dance between public and private speech feels more like a useful way to investigate this For our reading, Vanesa will be reading the part of Marcus, and I’ll be reading the part of Seth and the Stage Directions. Seth and Marcus speak to the audience. They are not walking.

Vanesa (02:27):

I’m Marcus Youssef. I’m a 51-year-old cisgender man, mixed race, Egyptian Canadian.

Ian (02:33):

I’m Seth Klein. I’m 52, also a cisgender guy and my family is Jewish. We’re friends.

Vanesa (02:38):

We’re walking

Ian (02:40):

Outside in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada,

Vanesa (02:44):

Ed Coast Salish territory

Ian (02:46):

On a cold day in late January, 2021 during the second wave of the COVID Pandemic, they speak to each other.

Vanesa (02:53):

Thanks for doing this.

Ian (02:55):

You’re welcome. Hey, just before we start, I just want to say I’m sorry about your dad.

Vanesa (02:59):

Oh yeah. I appreciate that, Seth,

Ian (03:02):

You were close.

Vanesa (03:03):

I guess. Yes,

Ian (03:05):

You’ve talked to me about him.

Vanesa (03:07):

He was a very powerful figure in my life as dads are, I guess.

Ian (03:11):

Yeah.

Vanesa (03:12):

Yeah. I thought we could just wander towards Trout Lake. That’s where I like to work.

Ian (03:18):

I’m happy with that.

Vanesa (03:19):

It’s so beautiful today. So sunny, can you introduce yourself in whatever way you feel like you want to?

Ian (03:26):

Seth’s introduction is likely to the audience. Okay. My name is Seth Klein. I most recently am author of a good war mobilizing Canada for the climate emergency for 22 years. Before that, I was the founding director of the British Columbia chapter of Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives,

Vanesa (03:43):

And over the last few years you’ve got a laser focus on climate change as an issue.

Ian (03:48):

I am very focused on the gap between what the science says we have to do and what our politics is prepared to entertain. Figuring out how to tackle that gap

Vanesa (03:58):

Is that the Green New Deal?

Ian (04:00):

I think the Green New Deal is a central and powerful model for bridging the gap.

Vanesa (04:04):

What is the Green New Deal? Give us a one paragraph summary.

Ian (04:08):

Okay, so the original New Deal, the Green New Deal, takes a profound crisis and meets it with massive public investment. It’s an ambitious plan to spend billions in new green infrastructure to electrify everything and create millions of jobs. Not sure. That was quite a paragraph.

Vanesa (04:23):

That was a very good paragraph.

Ian (04:25):

Thanks. Can I add The Green New Deal is about linking climate mobilization to tactically inequality. What I learned in my research about the effort to mobilize Canada for World War II is that it was actually hard to do with a typical propaganda go across the sea and go get Hitler. That works only to a point to truly mobilize people. The government had to promise that society or that this society people came back to was going to be different, which happened. Canada saw its first major income support programs introduced in the war, unemployment insurance in 1940, the family allowance in 1944, the architecture for the entire post where the state was written during the war. It was a pledge that the society people came back to was going to look different from the one they’d left. That’s how you mobilize everybody. It’s the same with the Green New Deal today

Vanesa (05:13):

And what’s the best argument against it?

Ian (05:16):

What’s the best argument against the Green New Deal

Vanesa (05:19):

If you had to choose one

Ian (05:21):

That it’s not realistic or feasible?

Vanesa (05:22):

What about the argument that keeps you up at night a little?

Ian (05:25):

Well, none of it

Vanesa (05:26):

Really,

Ian (05:28):

Really. I talk about it in my book. We’re all trapped by the legacy of 40 years of neoliberalism that has told us what is and isn’t allowed or possible. The powerful thing about an emergency, whether it’s the war or COVID, is that things seem politically or economically off limits. They suddenly become possible. If you said to Canadians in 1938, does the government have what it tastes to completely transform the economy has actually happened during the war? I’m pretty sure most would’ve said no. It’s going to happen with climate too. The only question is whether or not it will happen in time. That’s what keeps me up at night. Marcus maybe acknowledges the audience.

Vanesa (06:03):

I’m also conscious that some people who might watch what we’re constructing here are not from the wealthy industrialized countries. How did it impact what you’re talking about?

Ian (06:12):

That’s a hard one. It’s a fair question. The other piece of the legacy of neoliberalism is that it has undone our sense of our ability to go do grand things together. Maybe it’s wishful thinking, but history is full surprises of how quickly we pivot if and when we recognize emergencies for what they are and each society has to excavate its history for those relevant examples.

Vanesa (06:34):

So when I pitched this to you, I said, this year the theme is envisioning Get Green New Deal. And you were like, so this time you’re not going to write something Sonia Histic.

Ian (06:45):

Well, less dystopian,

Vanesa (06:47):

Right? You said less dystopian.

Ian (06:49):

Your last piece was very dystopian. This is a lot of artistic work that I’m going to say that again. There’s a lot of artistic work that tackles climate, but it’s almost universally dystopian.

Vanesa (07:00):

What’s your read on that?

Ian (07:02):

It’s understandable. When we think about climate, we imagine this terrifying hellscape that is likely to emerge if we fail to rise to the moment. But I’m also struck that a lot of the artistic mobilization for the Second World War was not like that. Even though they were surrounded by death and destruction, it was positive. It was rallying the public.

Vanesa (07:20):

I wonder if that’s artists not wanting to be propagandists.

Ian (07:24):

Yeah, you can’t tell artists what to do. I understand that. I think the Green New Deal needs to have a big arts component just like the original, I’m going to start this whole line over. Yeah, you can’t tell artists what to do. I understand that. I think the Green New Deal needs to have a big arts component, just like the original New Deal and in World War II artists walk this careful line. They were forthright about the gravity of the crisis, and yet they still imparted hope. I grabbed hold of the Canadian World War II story because I was trying to excavate a historic reminder of what we’re capable of and everyone’s got different stories to draw on. That invites us to say in the moments of existential threats or crisis, who do we want to be?

Vanesa (08:05):

Totally. Everybody goes through crisis. It’s a part of the human experience.

Ian (08:10):

Yeah. Hey, I want to say again, I am really sorry about your dad.

Vanesa (08:13):

Thanks. I appreciate that.

Ian (08:15):

End of play. Marcus Youssef’s play have been produced in more than 20 countries across North America, Asia, and Europe is a recipient of the Siminovitch Prize for theatre like Seth Marcus is based in Vancouver, the Unceded Coast Salish territory. Seth Klein is a public policy researcher. He was founding director of the British Columbia office of the Canadian Center for Policy Alternative CCPA and is now team lead of the Climate Emergency Unit, a project of the David Suzuki Institute. So Vanesa, what was the atmosphere like at the National Theatre Event, the 14th? What struck you most about how theatre makers are talking about sustainability?

Vanesa (08:59):

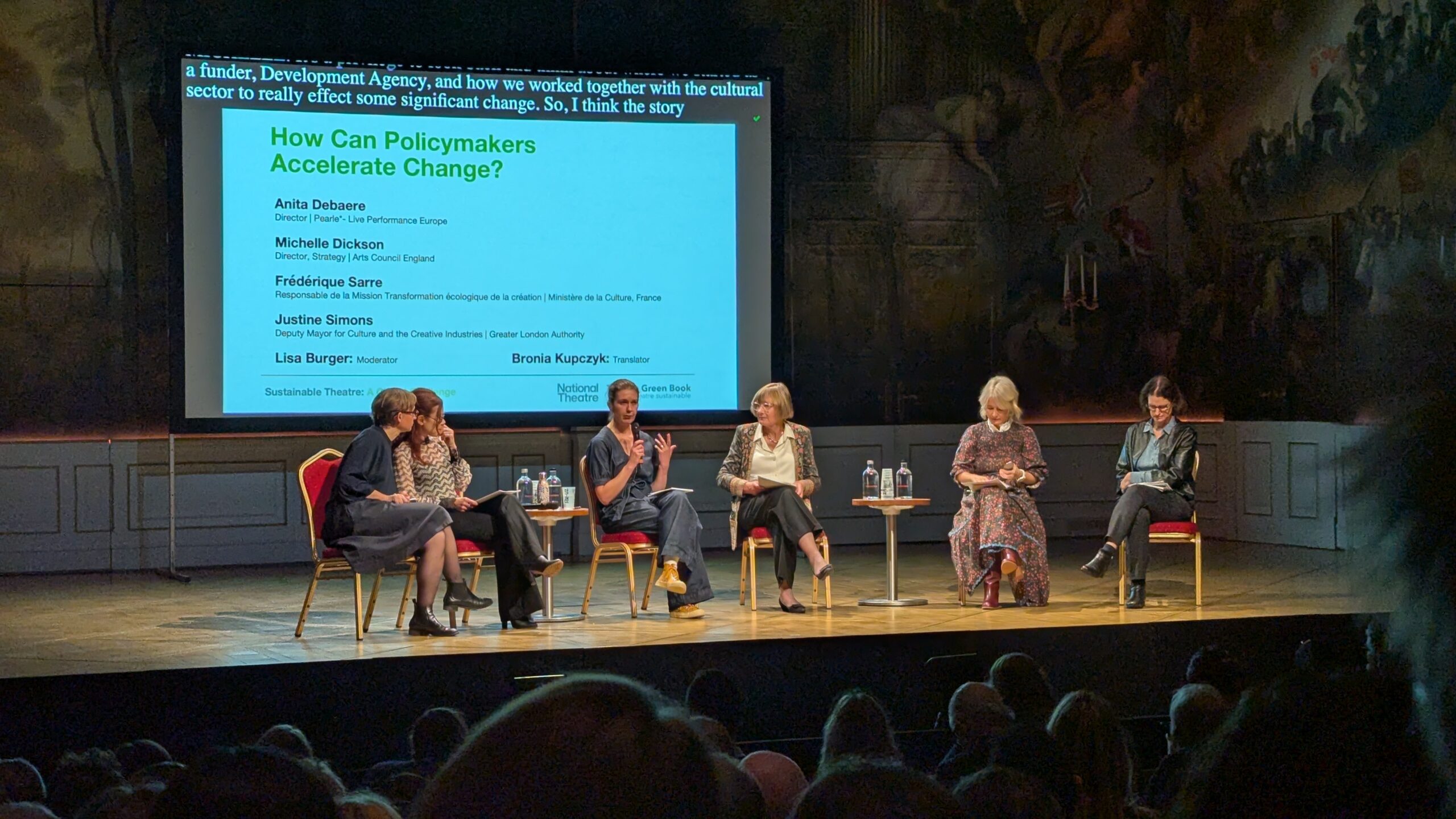

So to start with, I didn’t realize how many people had attended. It was sort of like a global call and it felt like we filled up a 500 people auditorium. It was so many people. The atmosphere felt very urgent and energizing and everyone was recognizing that sustainability is just not a side topic. It’s something that is touching every part of the performance and the arts and their role no matter what companies they came from, it was a wide variety of companies that are all involved somehow in one way or another in the theatre process. So some things that stood out, maybe how international the conversation was because there were people from all over the place, different countries. We grew up, we had Japan, we had Denmark, lots of you are from Europe, and it was sort like people were thinking beyond individual buildings were companies.

(09:51):

So they spoke about working across borders, across disciplines. There were serious discussions about sharing resources and sharing materials, and now companies that are now focusing on this, we had panels where companies spoke about exchanges talk between countries or touring with modular systems so that the local team can adapt and deciding productions and production workflows so that fewer things are single use. The national theatre actually brought out a short movie. Maybe we can actually link that later about how they’re reusing and how it’s sort of like they’re building this materials library and I believe that they’re one of the first ones are doing this. Another theme was the idea of multipurpose spaces and circular approaches. So one of the examples that the National Theatre did was a mental health flower garden that it also works as a flower farm for natural dyes. So this again is giving a space more than one task, so supports wellbeing and also production needs at the same time.

(10:55):

And that sort of thinking shows how sustainable theatre can be imaginative and degenerative and can be connected to different communities and different needs. So overall, yeah, the atmosphere was all planned. It was very honest. No one pretended that this transition is going to be simple or easy. We’ve had some really challenging and strong opinions from the audience and the questions that were, we were saying, well, how fast can we actually move? Are we ignoring the real elephant in the room? Why are we not sharing conversations between different rooms such as politics and arts and theatres? And as much as they were true, I do feel like gatherers like this ones are doing a massive amount of work trying to introduce people that do talk about policy and policy change.

Ian (11:38):

How did the Green book resonate for you personally as an artist, producer and someone building? Venue 13,

Vanesa (11:43):

To be fair, I met lots of people for the first time, many of them, and it does feel like everyone wants to make a change. Everyone was very excited to be there. The debates were well shaped, they were thoughtful and those were grounded on practice and the topics, they did speak directly to the future of how we’re going to make theatre moving forward. There was sort from now on, we’re going to do this still dwelling. So much in the past is looking at how things can be better now. There were several moments where the conversation turned to the international and European policy and we’ve had a few speakers, representative speakers and representative companies in panels and how the UK can still benefit from wider collaboration and by sharing standard co-productions, material libraries. And then also this common approaches to the circular practice. It did show that sustainability doesn’t follow borders, at least sustainability in theatre doesn’t have to follow national borders because theatre doesn’t really follow borders, especially when we’re talking about theatre and touring.

(12:47):

It can be quite a global movement. One of the things that resonated was that, especially with building Venue 13, was the idea that the Green Book gives a shared language and it doesn’t restrict the creativity. And by helping us rethink how we make tour and store the work and how we design the spaces, we will avoid a lot of waste. And that’s kind of like waste at the source. And as a producer, I found it very encouraging. It made me feel that we can actually do this. We can create a venue and a platform and support sustainability and it was real and in a practical way and it confirmed that the direction we’re taking a Venue 13 is a step, it’s like a right step in the global movement that believes that theatre can be inventive and it can be environmentally responsible at the same time.

Ian (13:34):

Were there particular sessions or people at the event that inspired you, ideas or commitments that you felt especially urgent or hopeful?

Vanesa (13:42):

Yeah, there are many people that are very inspirational. I’m going to be merging some names here, but a couple of them stood out I think for this question. One that really stayed with me was hearing Anita Dere, he drew this big powerful connection between the event and what’s happening globally right now, which is the COP 30 that happened at the National Theatre and the Cop 30 sort of happened at the same time, which is the Cop 30 was taking place in Brazil. She talked about how the timing wasn’t accidental, that the climate conversation and the theatre green book conversation that were part of the same movement. And I feel like she was one of the first ones and one of the only ones that actually made that comparison. And Anita said that something that really struck with me. She said, there are no boundaries in how we work anymore, but we do need methods and structures to help us achieve that.

(14:35):

And then she made reference to the Theatre Green Book as a fantastic tool for making that kind of boundary less collaboration possible. And then she explained how, so she works at Pearl and she explained the work that Pearl does with the national federations and the European Associations and how they mutualize this knowledge and the connect organizations by aligning international policy work. So she does say that culture is an international activity by nature and that we need that collaboration. And what I found really inspiring was how she described Pearl’s role Brussels, that they monitor the policy developments from European institutions or UNESCO institutions and international bodies. And then they translate that information and used that word intent. She said it’s like working with languages and they translate this policy so that we can actually understand one another and build a shared case. And she feels like this translation work opens doors not just as one individual, but because the collective weight of all of these organizations, they kind of come together and now they understand the conversation better thanks to these translations. And so she says the key was bringing conversations forward with openness, explaining what’s happening in each sector or region, listening to the differences and then using that to unlock new possibilities. So genuinely her chat was very inspirational. It made me feel genuinely hopeful. It was a reminder that sustainability in the arts doesn’t come from isolation. We really need to work together.

Ian (16:11):

How do you see your own role or our role at Venue 13 aligning with the goals of the theatre Green Book moving forward?

Vanesa (16:17):

So you might remember this Ian, and I’m going to bring you back to this actually. So there was another lady who was extremely inspirational and she was inspirational because in a way she is a little bit like me. One of the ideas that really resonated was it came from, again, a, so Sarah Morman, she’s the artistic director of head Suki to now, she said something very similar with what I said about Venue 13. So when Venue 13 became an all vegan venue, we had some people asking us how can venues be more sustainable? And I think I was half joking, but half seriously when I said that the reason why Venue 13 is that they’re all vegan venue, it’s because I’m vegan. And I said, well, if I’m going to have a venue and I have that power to make the decision, I’m not going to have it any other way.

(17:11):

So although that’s a small example in a way, I was trying to say that we just need a lot of little green dictators. And it’s a joke because I’m not a dictator, but it’s kind of like I had that possibility and I didn’t open it to like, oh, I wonder day if anybody else doesn’t want the venue to be vegan. I was like, no, we’re going to have a vegan venue. So it was a little bit selfish. And that reminded me to what Sarah said at the conference. She said she didn’t move towards sustainable design because he’s morphological and more virtuous, but she says he was a bit selfish. She says, it actually makes me more free. So sustainable practice opens up new materials, new methods and new ways of thinking, and also it becomes an invitation to explore, experiment and have fun and be more free.

(17:55):

So that really aligns with how I see our work at BSRT. So like Sarah, I want us to challenge our space limitations in, I want to make immaterial set designs or digital sonography or modular systems, and I want those approaches that make storytelling possible whilst minimizing waste. So minimal sets are environmentally responsible, they’re easier to tour, easier to source, and often they leave a lot of room for the imagination. Another thing that Sarah said that stuck with me was about the audience expectations and the audience experience. She talked about a moment working with the prop with stage blood, which is a prop that is very heavy, it’s messy, it’s hard to clean, it’s environmentally wasteful because you have to be poor more than what you need. And the alternatives were suggested, but I think as a team they realized that it didn’t look like blood.

(18:48):

So then they had to step away from the problem and ask, is anyone theAudience really believing that this is real blood? Of course not. So once they acknowledged that they could switch to a lighter, cleaner or more sustainable option without sacrificing the storytelling by giving credit that the audience will meet them halfway. So that’s the kind of shift that I want to do with Venue 13. I want to trust that the audience will actually meet us halfway, that the suggestions can be powerful or as powerful as realism and that we’re going to find creative solutions that can be greener. So yes, moving forward, our role is to embrace this spirit of experimentation for Venue 13, push for sustainable choices, expand artistic possibilities and support artists in imagining sets and systems that don’t rely on heavy materials or waste. So we want to align with Thea Green book as a creative toolkit that encourages us to rethink what’s possible, what’s also on stage, and what’s possibly storytelling whilst holding sustainability at the center. So Ian, you have contributed to Theatre Green book in the past. Can you explain what was your involvement and how you see this impact on the sector?

Ian (19:56):

Yeah, I got involved in the theatre Green book I think relatively early on. The sustainability and theatre has been something that I’ve been involved in for quite some time actually. I think that it’s officially, I can date it to at least 20 years at this point. And so it’s something that as a niche that I’m known for. So as they were being written, I did get a chance to review them and make contributions and comments on them. I think that in the long list of contributors are looking, if you look through the credits that my name’s someplace in there as well. And so that’s looking at that eye of thinking through these systems and thinking through the way that people are producing theatre and how they’re doing that in different contexts and in different places and providing that sort of perspective, a variety of perspectives.

(20:50):

I think that one of the things that’s true about sustainability in theatre in my experience is that it’s slightly different for everybody. It’s very dependent upon the context in which you’re working. I think that one of the most common questions that I’ve received over my career is what is the most sustainable thing that I can do as a theatre maker? And the first answer is actually always the same. And then everything else is sort of context specific. And the first answer is to make more art that engages with your audiences. And I used to say it a little bit more sarcastically, which is to make good art, but then you had to get into a conversation what makes it good. But when you start getting people together into a space and sort of amortize the impacts, the environmental impacts of those people, the sustainability metrics tend to be good if you’re looking at it from an impact or a metric measurement frame.

(21:48):

And really the best thing that you can do is get a bunch of people together into a room and have them have a shared experience. And then the thing that theatre also does is that they’re having that collective experience and perhaps you’re modeling different ways of being in the world. That’s the biggest impact that you can have. But then once you get past that, it really depends on the resources that are available to you, wherever you are, how things function, how your community works, what you’re building is what the show you’re putting on is and things like that. One of the things that I think is really important about the Theatre Green Book itself is the number of people that were involved in taking a look at it so that it wasn’t just bias towards one place or another, but was looking at here are things that everybody can do, but here are also a lot of questions that you can ask or here are things that if they are appropriate in your context. And this still doesn’t necessarily, it’s not the right resource for everybody. It does look at buildings and production in a way that a lot of people work, but there’s a lot of people that won’t. And I think that’s true for every sort of guide or tool that comes out in this topic. So I’m just one or my opportunity was just to be one of the many, many voices that helped to provide nuance for it so people could find their place in the conversation and find solutions that work for them within the theatre Green Book.

Vanesa (23:09):

That’s amazing. And from your perspective, what are the biggest challenges theatre companies face in implementing the Green Book standards, especially around set design and materials and waste?

Ian (23:22):

We have a lot of really enshrined practices in theatre. Part of this is that we come out of sort of an apprentice sort of model anyway. People get trained through doing. There’s not really one way in which people get into theatre. One of the things that I’ve always enjoyed over the course of my career is just hearing how people got into theatre. Because like myself, I didn’t set out, I didn’t go to university originally through theatre. I went to study architecture. I got involved in it sort of as an extracurricular activity. I found it very satisfying, decided to work for a bit and then went back to graduate school for it. And I’ve sort of dedicated myself to theatre since. But it was a process of how did you decide to get here? And so part of that means that it’s very social, like the way that one gets trained or comes up through theatre tends to be very social.

(24:15):

But what that also means is that we learn ways of doing things and we replicate those because they work. And there’s also utility to that because when you are doing something, we are working to very hard deadlines. We’ve committed, we’ve sold tickets, audience is going to come through that door, so you need it to work. There’s this idea of it being show ready, which you could also phrase this, the classic adage of the show must go on, but the show also is committed to open. It’s a big deal when it doesn’t. So when you’re doing that, you come up with ways of working that don’t put that into jeopardy, that you know that the audience is going to get the experience that you intend them to. It might not be identical every night, but you’re trying to get as many of the boundaries or many of the potential roadblocks or deviations from how it works as possible.

(25:08):

You end up working in very similar way is from project to project. You’re having to do that within a time crunch. And so you don’t have a lot of time for experimentation in there. So I think the biggest challenge that theatre companies face is that there are ways that work, there are ways that can accomplish what we are setting out to do whatever the concept is, whatever the artistic prerogative of that piece. And we’re trying to do it under very strict and sometimes very limited timeframes. And so it’s very easy to rely on ways that we know will work even if those aren’t necessarily the most sustainable ways working. And where do we find that time to actually be able to change what we’re doing. It’s one of the reasons that as you were talking about the communication, the collaboration is so essential because there’s not one company that is going to be able to really focus on all of the solutions or the comprehensive process. And as I was saying, it’s going to change every time. It’s going to be different for every show, for every company. And so having something like the theatre Green book that has some standardized advice that you can start from in the way that you’re conventionally working becomes extremely useful around set materials waste so that things that work so you can have that same confidence and then adapt it for your specific context and you’re that much farther ahead.

Vanesa (26:31):

And so I’ve been hearing quite a lot about that. We have to reuse, we have to reuse, we have to recycle, we have to reuse. But another thing that I’ve heard was if you have a set and a designer designed this set and another in the spirits of reusing or recycling it, if another play reuses that set, would it be a problem for the designer that would they be feeling saying some licensing over that? Can they license or actually say that this set was made by me and then what happens someone else who uses that?

Ian (27:03):

So coming first from the idea that we’re using our material waste is reducing what we’re making, that is one approach that you can take. You can definitely say can it be as sufficient with the material as possible? And sometimes you’re forced to do that regardless, budgets, time, et cetera for it. So it’s not just the green aspect of it or using less material or different types of materials that might require different ways of working, which might take more time or might be more expensive for it. All of those have impacts on the reused, recycling and reduced waste. I think that’s the most impactful choice that I’ve seen is really simple. And it is taking a look when you’re going through the process of budgeting or costing a production is just adding a column for end of life. This is something that so many processes that I’ve been involved with are not thinking about a show ending in a commercial sector.

(27:58):

It almost makes sense because hypothetically you have a hit show and it runs and runs and runs and runs. So you’re not thinking about disposing everything. But I know of a number of designers who, part of what brought them to this topic is because they would be working in that context and an official Broadway run would open and then close within a week or two and then it’s all in the dumpster. But you were sort of imagining that it might be the next wicked or cats and run for decades. And that is sort of an edge case for it as well. But in most theatre production we’re talking about a few weeks and so it’s pretty easy and actually surprising to me that we’re not talking about end of life at the beginning. Oftentimes in the traditional process, you go through the costing process, you build the thing and then once it’s open you’re like, okay, now we have work through our strike plan, figure out how we’re going to get it out of the space.

(28:48):

Now that we put it in there, we have to transition to the other thing. But if you move that to the beginning, move that to the same place when you’re costing, just add that column that says, where’s this going to go at the end? And are we cool with that? We have all this wood. Is that what we want it to be? We have all this steel. What’s going to happen with it? It allows you to factor it into your decision making. And so if people are familiar with the hierarchy of safety and hierarchy of guarding, the best way to mitigate most problems is to just eliminate them. So if you eliminate the program that you have all this waste by saying, I know where it’s going to go at the end and it’s not going to avoid everything. That’s been something that it has been surprisingly effective and sort of everybody can do that too because it’s not a use this or use that.

(29:31):

It’s not advocating for product, it’s being conscientious there. The other part of that around reuse when it comes to intellectual property is a really interesting question. And in a lot of places, and I know this is true in the conversations that I’ve had in both the US and Canada, that it is something that creates a bit of limitation. I’m on the board of the, well, it’s been bifurcated since we unionized, but involved in leadership with stage designers in Canada with the associate designers of Canada helped with the unionization. So now we have a Union ii, a D, C 6, 5, 9, and we also have a national art service organization that supports the design profession. And I’m still on the board of that. And one of the projects that we have been looking at is looking at our contracts as we negotiate the contracts with a lot of theatres that our designers end up working with and they have really good IP protections in it.

(30:22):

But if you look at that language, it tends to say that it’s protecting the full set manifestation of it. And then we know that the individual component parts for it, a piece of material or even if it’s assembled into something that’s relatively common or a useful thing that that’s not protected, but you end up in this huge spectrum of in-between space where people are a little afraid of it and really no one wants to, the way that it would be figured out is if it went to court and no one wants to do that, no one has the money to do that. So one of the proactive things that we’ve been doing with the A DC and with our contracts is offering a way for designers to articulate, here’s the boundary of what I think is mine and what I will allow you to do with it. So you don’t have to get into the legal battle of it. It’s about being proactive about where you want things to be and being proactive about how to mitigate the waste.

Vanesa (31:16):

Yeah, okay. So it sounds like stronger communication, leading the communication from both from the part of the people that are going to reuse the stage and also from the designer to say, I don’t consider this mine anymore if you do it in this way or another way. And so that’s really interesting. I think you might have answered some of this question already, but what role do you think workshops and trainings such as carbon literacy or sustainability training play for production teams?

Ian (31:45):

I think it’s always useful just to know more. That is what I teach in my university position too. I teach sustainable staging and also approaches the echo sonography, how it impacts design as well. And I do work around carbon literacy, sustainability training, how to evaluate processes and not from a sustainability lens and that sort of value setting for it. And I think that people have, especially because it has to do, a lot of people choose to do this because they value it. And so a lot of people will look at what their options are and they have an innate sense of how to improve things. But I think giving people the tools and the education, even if it’s just a point towards resources, becomes really useful to expand that, to keep people thinking about it, to understand that they don’t have to figure everything out, that there are ways that they can be supported in making this change and meeting other people that can help them around

Vanesa (32:41):

How should theatres communicate their sustainability efforts to audiences so that the green practices become part of their identity or not just a checkbox. And I’m asking this because sometimes you go to a performance, for example, say they have a very minimalist staging. Would you feel like the audience may feel like the company are trying to save money, or would you say that they would understand, oh no, this is actually a green effort or a green initiative, or how is it best to communicate this?

Ian (33:09):

I think particularly within the arts and especially within theatre, where the disconnect happens is when the approaches to sustainability are at odds with or just not aligned with the actual art itself. All the successful sustainability projects that I’ve been involved with in an artistic context have been successful mainly because the approach to it became intrinsic to the way that we were working and was very core to the type of art that we wanted to make. Now that doesn’t mean you have to make everything be a play about the environment. It doesn’t have to be a play about sustainability, but that we’re very intentionally thinking about the way that we’re working. And at this point I think that it’s pretty easy to say that every play that you see, every performance that you see is in the context of climate change. It’s part of the world that we’re in, so it is one of the reads that we have on anything that’s happening regardless of where you sit on the topic with it.

(33:59):

So I think that making sure that it has integrity in that regard, it’s related to what you’re actually doing. I have seen some theatres say like, oh, we’re going to go with minimal things and it’s actually more of a budget thing, but they’re like, oh, it’s also green, and they did take into task for it a little bit. Like going green does not mean taking things away. It means thinking about why you’re using what you’re using and perhaps doing things differently. So I think that communicating to audiences are being honest and having integrity and making sure it aligns with what you’re actually doing that doesn’t look like you’ve just added it on.

Vanesa (34:37):

And can we talk about the Center for Sustainable Practice in the Art with the CSBA, you oversaw the Creative Green Tools Canada program, which is based on the same program as Julie’s bicycle, so this has recently you had to wind down though, and can you tell us a bit about this and what the differences and perhaps the challenges are with this type of work between the UK and Canada?

Ian (35:01):

Yeah, this was a hard one in that for many years, once Julie’s Bicycle, which is a charity in the UK that has built amongst other things, they have lots of programs but has built a platform for doing emissions tracking within the arts and as part of the national portfolio under Arts Council England, it’s provided and supported. So when you get funding through Arts Council England like operational funding, you’re required to do environmental reporting of some variety. You have to have an action plan and then you have to do some reporting that says that you’re there. And so they support the existence of the tool to allow that to happen. Many places have tried to replicate that program. I think it has varied nothing has quite had the staying power of the special relationship between Joys, bicycle and Arts Council, England, even in the other nations of the uk, they have different approaches to it.

(35:58):

We have a close partnership with Culture for Climate Scotland, formerly Creative Carbon Scotland, and they have other tools. They had looked at that tool early on as well, so we got support to bring that in. There was systemic excitement around it from the Department of Heritage and the Canada Council for the Arts back in 2019 and 2020. And so for about five years, we went through a couple of years of first adapting it to a Canadian context, really customizing the way that people interact with it though a lot of the backend calculation and what it tracks so that you could compare with other localities is common. And then we operated for three years only Quebec as a province and with their provincial funders started to integrate it into the funding scheme. And so there was a mandate for it and other provinces didn’t. It didn’t happen the federal level, I think people might’ve been looking to go in that direction, but it wasn’t able to be sustained with the amount of support that needed to actually properly grow.

(36:59):

And with it tied into more sort of discretionary and strategic approaches to funding as opposed to a specific grant or a specific long-term commitment, it was always a challenge to keep up. So in this last year, as people were reevaluating their budgets, even the commitments that we did have, which didn’t quite get to the full amount that was required to keep it operational started to decrease. And so eventually we had to make the hard decision to retire it and eventually ended up having to dismiss the staff that was associated with it just as this, we couldn’t financially sustain the program. And it’s interesting because I think a lot of people are sad about that, but it is something that is not necessarily built into our system. We’re trying to do systematic change there and it’s not even happening in our organizations in the same way that somebody has to do it.

(37:51):

It’s still tied to people wanting to do it, and that makes it a challenge because it’s something that you can choose to do or not, you don’t need to work that way. There’s not an expectation at this point that that’s the way that we’re going to work. Whereas there’s other values that we have embedded into the theatre profession, health and safety, a lot of equity approaches and access approaches, those are now expectations. And there is both legislation, there’s cultural policy, there’s funding that supports those aspects of it, and we haven’t quite gotten there the same way with sustainability. Part of that might be just because it’s just not as immediately visible or there’s been a lot going on in the last few years. So it’s an interesting juncture because it was great to see. I had originally hoped that I would be able to be at the event for the either Green Book as well, but it didn’t come together because we’re facing other types of structural challenges and sort of where that puts us as also.

(38:52):

So then what is the best thing for us to do? What is our best approach to take to this topic? If people think that it’s valuable and they want to do something, but maybe emissions isn’t the right thing for, in this case for Canada and perhaps for other places, what are the things that we can do? We’ve seen a lot of initiatives come and go. The CSBA was founded in 2008. I’ve been working in sustainability and theatre, if not the arts, more widely since 2005. And we’ve seen lots of up and down cycles of when people are supporting this work and advancing. And part of that has led to initiatives coming and going, and my approach is always to be like, I want to see something stick where no one benefits from being possessive or from saying, this is my thing. No one’s getting particularly wealthy doing sustainability within the arts.

(39:44):

And so I think that it’s interesting to see that we’re the contrast point where in the same week or within a week span, you have this event at the National Theatre celebrating the Theatre Green book and its translations with its international partners. And it’s sort of sustained growth over the last few years with the challenge to initiatives in other places and other jurisdictions. The Creative Green Tools Canada program being an example of that. We’ve seen a lot of ups and downs and you can imagine that it’s challenging within the us and I know that there was representation from the Broadway Green Alliance where a lot of the leadership work is happening in the US also at the Theatre Green Book event. So it’s an interesting time to see the shifts in where the priorities are going, especially as we get to 2030 when a lot of the commitments articulated in those sustainable development goals have important benchmarks and deadlines that they’re trying to hit.

Vanesa (40:43):

Thank you for actually touching into those challenges. And yes, like you said, bringing it back to the deadlines, the 2030, the SDGs and bringing light into these issues. And like you said, maybe society has not been embedded in theatre like other things have that have more stronger policy and stronger funding and granting for and that should change as we build on Future 13. I do know we’re not going to go into this too much today. We probably will dedicate a full episode to this when we’re very excited to talk more about it, but what lessons from the theatre Green Book do you think are most relevant and sustainable for sustainable arts nonprofit like we are planning to be?

Ian (41:24):

I think that, I mean, the most important thing that has been my experience is just building the relationships and reaching out to people and saying, how can I help? I think that’s part of the ethos behind Future 13 and why we thought that made sense to create a sort of not-for-profit service approach where we’re trying to help people produce, we’d like to be producing a Venue 13. We can embed the values within our own small venue that operates during the Fringe Festival. If there are people that are interested in what we’re doing, how do we share that out? How do we help people do that? And so I think that the Theatre Green Book actually does a good job of helping people understand what the communication is. It’s in a really good job of building coalition around it. And so I think that both the principles that are in it, and so its approach to sharing is an important part of what I’d hoped for Future 13 especially, because one of its purposes is to help artists within a very specific context within preparing work for the festivals to do it a much more sustainable way to take advantage of the knowledge that we have and the way that we run the venue, whether or not they’re performing with us or not.

Vanesa (42:37):

Thank you, Ian. So there we have it at attending the Theatre Green Book event was a reminder. The sustainability theatre isn’t just an ideal and it’s something that we can build into in every part of how we work, but also it requires ambition, humility, and the willingness to change and also to collaborate.

Ian (42:55):

Yeah, absolutely. The Green Book offer is practical shared standards, but it’s really up to theatre makers to use them, adapt them, and hold themselves accountable for us at Venue 13. This is not just a mission, it’s our responsibility.

Vanesa (43:09):

As we said. Speaking of Venue 13, we are very excited about our next chapter or an extended chapter to Venue 13, which would be Future 13, our sustainable arts nonprofit. We’ll be talking more about that in our next episode and how we will put the Theatre Green Book principles into action.

Ian (43:25):

So until next time, thank you for being here for caring about theatre and the planet and for being part of this community.

Vanesa (43:31):

See you soon.

Ian (43:37):

On today’s episode, you heard Ian, Kurt and Vanesa Kelly, co-directors of Venue 13. Our music for this episode and all episodes is from Dusty Decks, which we licensed via academic sound. Thanks for listening. If you enjoy the episode, please subscribe and leave us a review. You can reach us at podcast@venue13.com or follow @venue13fringe on all socials for full transcripts. And to check out our past episodes. You can see those on our website at venue13.com.